On Homevideo: See It On Any Screen

One of the great things about growing up in New York during the 1970s was experiencing the films of Sidney Lumet, who died today at the age of 86.

Lumet had been making great pictures since the 1950s; his first film--his first film--was 12 Angry Men, and he went on to direct classics like The Pawnbroker, Fail-Safe and the screen adaptation of O'Neill's Long Day's Journey Into Night. But the zeitgeist of the 70s, and particularly the New York of the 70s, intersected with Lumet's talents in an extraordinary way. He turned out a series of films that matches the streak of any other American filmmaker: The Anderson Tapes, Serpico, Dog Day Afternoon, Network, The Wiz, Just Tell Me What You Want--not to mention, during the same period, such very fine non-NY movies as Murder On the Orient Express, The Offense and Equus. (And in his spare time that decade, he managed 2 clunkers: Child's Play and Lovin' Molly.) Along with Martin Scorsese and Woody Allen, Lumet was one of the supreme chroniclers of the tumultuous Big Apple on film.

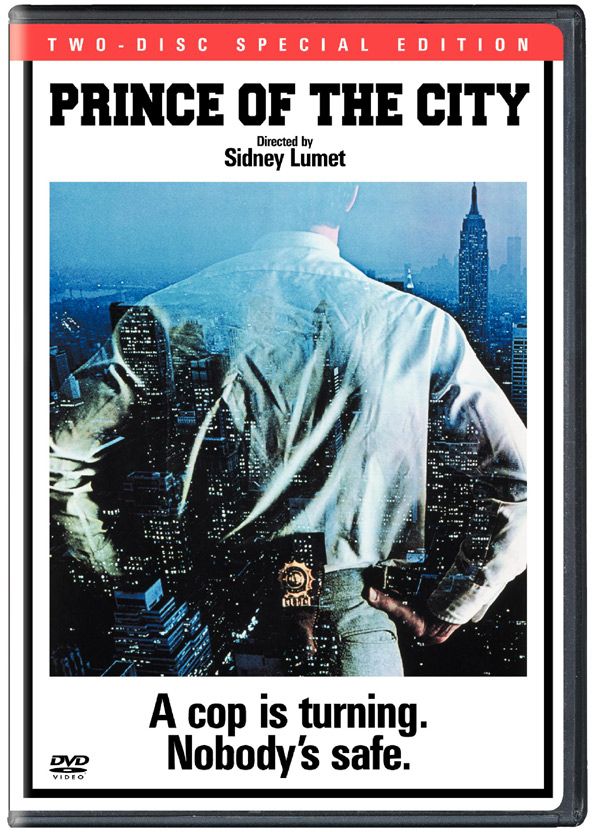

His masterpiece, though, was made shortly after the turn of that decade: PRINCE OF THE CITY. Released in 1981, it wasn't one of Lumet's more successful films at the box-office. Saddled with a demanding 167-minute running time and a storyline and structure that required close attention, Prince only made $8M for its studio, Orion (in the same summer the same studio made $95M from the original Arthur). It didn't turn Treat Williams into a Pacino-sized superstar, as it was supposed to at the time. It didn't win any Oscars (although Lumet did win Best Director from the NY Film Critics Circle, and the film won at the Venice Film Festival). But it's a seminal work in the history of its genre: one can't imagine Goodfellas or "The Wire," among others, existing in their present form without it.

Lumet, who revered good writing, took a screenwriting credit for the first time in his career on Prince (shared with Jay Presson Allen). The film was based on a nonfiction book by Robert Daley, and told the fictionalized story of Danny Ciello (Williams), a cop who served on an elite New York narcotics task force that was both hugely successful and utterly corrupt; threatened by Internal Affairs, Ciello ultimately informs on his friends. In telling his story, Lumet and Allen expose complex layers of the New York and federal justice system, while delving deeply into the moral issues Ciello faces when he becomes a "rat."

When talking about Prince of the City, one has to begin with the spectacular ensemble cast, perhaps the ultimate expression of Lumet's genius for casting. Lumet's own career started as an actor, and many of his films are showcases for ensembles: 12 Angry Men, Murder On the Orient Express, The Group, The Seagull, all the way to his final film, Before the Devil Knows You're Dead. Even in his star vehicles like Dog Day Afternoon and The Verdict, the protagonist is surrounded by a pitch-perfect supporting cast. He outdoes himself on Prince. The cast may include Jerry Orbach (pre-"Law & Order"), Bob Balaban and Lindsay Crouse, but mostly it's a collection of character actors, people whose names are less familiar than their faces and voices: Richard Foronjy, Carmine Caridi, Norman Parker, Paul Roebling, James Tolkan, Ron Karabatsos, Lane Smith, Peter Michael Goetz, it goes on and on--perhaps the greatest collection of New York character actors ever in a single feature film. And each one of them is indelible within the broad mosaic of Prince's story.

When talking about Prince of the City, one has to begin with the spectacular ensemble cast, perhaps the ultimate expression of Lumet's genius for casting. Lumet's own career started as an actor, and many of his films are showcases for ensembles: 12 Angry Men, Murder On the Orient Express, The Group, The Seagull, all the way to his final film, Before the Devil Knows You're Dead. Even in his star vehicles like Dog Day Afternoon and The Verdict, the protagonist is surrounded by a pitch-perfect supporting cast. He outdoes himself on Prince. The cast may include Jerry Orbach (pre-"Law & Order"), Bob Balaban and Lindsay Crouse, but mostly it's a collection of character actors, people whose names are less familiar than their faces and voices: Richard Foronjy, Carmine Caridi, Norman Parker, Paul Roebling, James Tolkan, Ron Karabatsos, Lane Smith, Peter Michael Goetz, it goes on and on--perhaps the greatest collection of New York character actors ever in a single feature film. And each one of them is indelible within the broad mosaic of Prince's story.Through the films and TV shows that have followed Prince of the City, we've grown more accustomed to stories that probe the morality of informing, but at the time it was a startling point of view for the movies. One of the reasons Prince failed at the boxoffice was that people expected it to be the follow-up to Serpico, where the morality was clear-cut: Pacino was a hero, and the corrupt cops were murderous scum. Prince has an infinitely more complex point of view. Ciello thoroughly enjoys the fruits of corruption, and his friendship with his partners runs deep, even though he knows what they're all doing is wrong. Conversely, the "good guys" who want to prosecute the dirty cops are often callous and untrustworthy. Late in the story, when Ciello is caught between his friends and the law, his loyalties are genuinely agonized, and so are ours--we don't know what we want him to do, and Williams' unheroic performance makes the situation even more tortured. Audiences, then as now, tend to prefer a more straightforward view of right and wrong.

Apart from the glories of the script and acting, Prince is one of Lumet's most beautifully made films. It's shot in what seems like a zillion different New York locations, all of which look superb as filmed by Andrzej Bartkowiak, and the extremely complex editing scheme is handled by John J Fitzstephens; Paul Chijara provides the spare and effective music.

Apart from the glories of the script and acting, Prince is one of Lumet's most beautifully made films. It's shot in what seems like a zillion different New York locations, all of which look superb as filmed by Andrzej Bartkowiak, and the extremely complex editing scheme is handled by John J Fitzstephens; Paul Chijara provides the spare and effective music. It is, of course, tragic that Sidney Lumet won't be around to give us more even films, but there is some comfort in the fact that he was still doing vibrant work in his 80s (Before the Devil would have been a remarkable film from a man in his prime, let alone a director who was 83 at the time). And, of course, we will always have the film's he's left us. Prince of the City is a great work of art from one of the kings of New York's film legacy.

0 comments:

Post a Comment